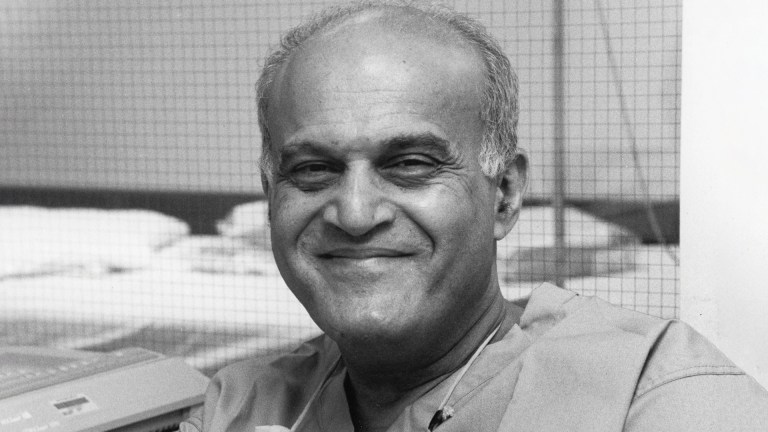

“We haven’t made progress nationally,” Michael Marmot, one of the UK’s leading public health experts and author of the landmark Marmot Review, told Big Issue. “It was predictable that we would handle the pandemic poorly, and we did, because we’d handled society poorly pre-pandemic, and it was predictable that we’d continue to do that.”

Marmot has previously complained that Conservative government had been unwilling to meet with him to discuss what needed to be done. As leader of the opposition, Keir Starmer namechecked Marmot in a speech and pledged to make England a “Marmot country”, tackling the social inequalities which influence health.

“So far, they don’t appear to have rode back on that, so they’re open minded about it,” Marmot said. “I’ve been invited to talk to senior people, civil servants and technical advisors, in a way that I wasn’t in the previous 14 years. They want to hear, and that’s already a change.”

He added: “The previous government talked about rolling back the state, making it smaller, more efficient, getting rid of migrants, anti-woke. They never mentioned health and wellbeing as outcomes of government policy.”

Clare Bambra, professor of public health at Newcastle University, said it would take a whole-government effort to address the inequalities in health which have built up – and that ill health cannot be reversed as easily as economic inequality. Will progress be made? “In July, I would have had a totally more optimistic take on that, but let’s be honest the last six to eight months have not inspired,” said Bambra, pointing to a lack of funding for the government’s new Child Poverty Strategy. “How the hell does that happen? How can you reduce poverty without money? I don’t understand,” said Bambra. “That would be a disappointment, for sure.”

If the moral stain of poverty shortening people’s lives does not convince, perhaps reducing people to economic units will. Health inequalities are driving the UK’s surge in working age health-related benefits, new research from the Bayes Business School at City St George’s University of London has found. Those in the poorest areas may experience poor health up to 21 years earlier than those in rich areas. In Blackpool, healthy life expectancy is 53.5 years, compared to 74.7 years in Rutland. Improving healthy life expectancy, professor Les Mayhew, who carried out the research found, would allow the UK to cut income tax by 2.4%

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“You get large numbers of people suffering from long term illness and disability, who are also economically inactive. That drives up the benefits bill for the country as a whole, and is a big problem in terms of holding back the economy as a whole. It’s almost like a barrier to improvements in the economic well-being of the country,” said Mayhew.

Short-termism in politics is a barrier, he said: “People now have a very good understanding of all these things. But the levers that you have to pull don’t have an instantaneous effect. Smoking prohibition would take 20-30 years to work its way through to improvements. But governments are only in power for five years at a time.”

Mayhew added: “It goes right to the heart of everything. Improvement depends on making progress across a wide range of fronts. There’s no doubt that Covid exposed some of the things we’ve seen. They were always lurking but they’ve become much worse.”

These health inequalities are all too visible for Dahaba Hussen, who works in Tower Hamlets with community organisation Coffee Afrik. The borough has a child poverty rate of 48%. Overall, 41% of its residents are in poverty. Its premature death rate is the third highest in the capital. This, said Hussen, has its roots in how poverty plays out every single day. “Poverty has a significant cause and correlation with severe health difficulties,” Hussen said.

“A lot of the time people have other concerns on their mind, other competing factors like putting food on the table, they don’t even have the space to think about putting their own health first,” Hussen said.

Hussen added: “A lot of the young people who live in Tower Hamlets are actually afraid to leave their homes because of the threat of gang violence, and the threat of being recruited. They feel like they can’t even socialise because they don’t know who they’re talking to and what their intentions may be.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

The consequences are clear, said Hussen: “If we have this generation who’ve given up on school, who don’t know what they want to do work wise, who don’t feel inspired by their surroundings, what’s going to happen to them? This is the next generation. These kids are between 12 and 18. We have a real crisis on our hands.”

Action to avert the crisis is being taken locally. Since Coventry became the first “Marmot city” in 2013, there are now over 50 Marmot communities across the country, said Marmot: towns and cities committed to fight health inequalities. Interest has grown in recent months, Marmot added, and as he spoke to Big Issue, emails kept landing in his inbox from local officials around the country. That week, he was set to speak to Bath, Fife, and Medway in Kent. Local progress, he hoped, could push the topic up the national agenda.

In London, the introduction of the Ulez clear air zone has delivered for disadvantaged communities. Among the most deprived communities living near the capital’s biggest roads, there was an 80% reduction in the number of people exposed to illegal levels of pollution. Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, whose daughter Ella was the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a cause of death, says the success of this has allowed her to make the case to Manchester mayor Andy Burnham and his Liverpool counterpart Steve Rotheram. She now believes air filters in schools can be the next frontier. “Hopefully, by the end of Sadiq’s tenure, all schools in London will have filtration,” she told Big Issue.

Kim McGuinness, the mayor of the North East – where child poverty rates are the highest in the country – came into office and launched a plan to tackle child poverty in the region, saying local action could fight the issue. McGuinness launched the country’s first Child Poverty Reduction Unit in August, and said the plan would be “tailored to what local families need”.

For Hussen, who sees political neglect in her corner of east London, listening is key. “A lot of the time when people think about health inequalities, and how they improve specific communities’ health, they do so without collaborating with those communities. Any plan moving forward needs to be done with the communities in mind, and in collaboration weith them,” Hussen said.

“There’s a real disconnect between government, public health bodies, and communities. It will require all three working together effectively in order to improve people’s lives. This is a political choice. There’s not really a real reason for people to be suffering.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more. Big Issue exists to give homeless and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy of the magazine or get the app from the App Store or Google Play.